Interview with HMP Birmingham Artist In Residence

Niki Gandy is Ikon’s Artist in Residence at HMP Birmingham. James Latunji-Cockbill, Ikon’s Producer, Art in Prisons, interviews the artist about their residency at HMP Birmingham.

Why did you want to take on the artist residency at HMP Birmingham, a large Category B prison serving the local courts?

I am currently about halfway through a practice-based PhD, with my research exploring the sensory relationship that we have with the passage of time, so where better than a place of incarceration to broaden my understanding of the impact of temporality on health and wellbeing? The working title of my thesis starts with the words “Inside Now”, so there’s an irony to the fact that my research has now moved “inside”.

As an artist educator, I’ve taught all ages and demographics in various settings, from private schools to universities, secure units to community workshops. Given the opportunity to move my practice – both creative and educational – into a prison, I was well prepared for the challenge.

HMP Birmingham is a particularly interesting place to work. As a proud Midlander from a working-class background, there’s a degree of shared experience and understanding. I was excited to take on this residency in part because out of the three prisons that comprise the Art in Prisons programme, this is the closest geographically to Ikon. The residency is a means of working with my local community, installed in the prison under the remit of reducing reoffending. I am aiming to give prisoners the skills, space and autonomy to explore art on their own terms and provide them with an alternative view on life. If we can do anything to reduce recidivism, that can only be a positive thing for the whole community. The research we are undertaking into the impact of art education on health and wellbeing is really important in this respect.

You undertook several workshops at HMP Grendon in 2023, working with prisoners to make a series of impressive pinhole photographs which are now permanently installed in the prison’s corridors. Did this experience inform your approach at HMP Birmingham?

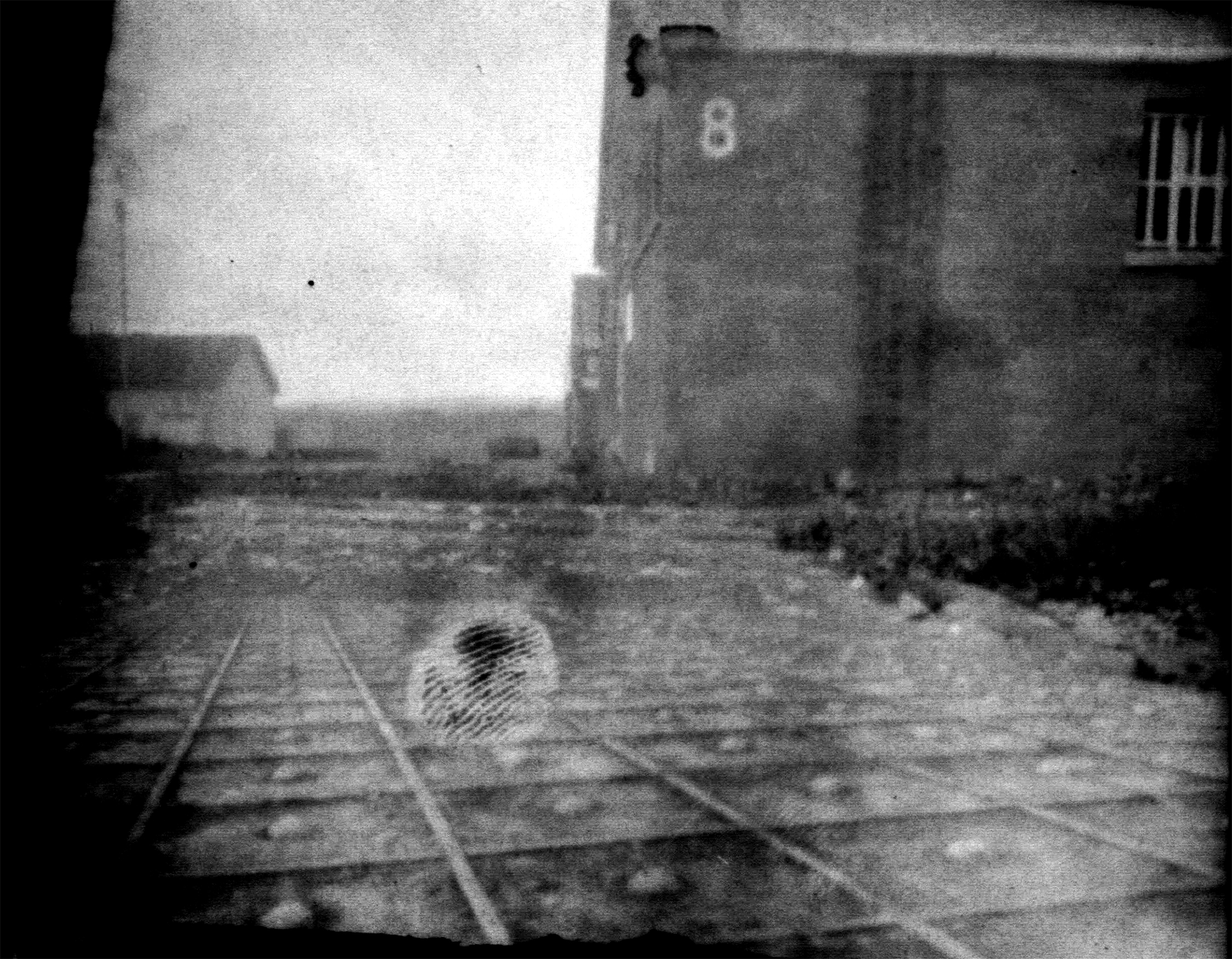

Grendon is such a special place, it was a really valuable experience to work there. It seems unusual to walk into a prison and feel comfortable straight away, but I learned as much from those workshops as the group, if not more. It was a challenge from the outset to work within the limitations of a prison setting to produce photographs. Working with photographic chemistry, in this instance using a process called Caffenol with chemicals made from coffee and vitamin C (both benign and readily available in prison). We turned the gallery space into a darkroom for the duration, working really spontaneously, ripping photosensitive paper to fit cameras made from coffee cups. The results had a stark quality to them, with some producing relatively sharp images of the art studio’s exterior. I am proud of that work and happy to know they are on permanent display.

This method is not something I have been able to explore at HMP Birmingham yet – it is a completely different prison with different security criteria. However, pinhole photography is very much a part of my proposed work here, if not the workshops I am producing with prisoners. I’ve used the Grendon images as examples to gain security clearance for my own work, so they are very much part of the process. The Head of Security is a keen photographer so understands and is supportive of the method.

How does the residency fit with your doctoral study – will your work in carceral environments inform your research?

The residency is likely to generate a case study or chapter in my thesis, enabling me to apply a methodology to a new setting. There are various strands of work that comprise my practice, all of which are in some way unstable. Duration unfolds upon the work to enable it to continue to self-generate after the point of making, often to the point of self-destruction. I have been working on a self-devised process that allows an image to appear over time if exposed to light. Imagine a beautifully framed entirely blank piece of paper on which an indistinct image of an inmate gradually appears, long after a sentence is served. The residency is the perfect opportunity to test out the methods I’ve been working with in a purely experimental fashion and under controlled conditions. Above all else, it enables me to use my work to problem solve, to think through real world issues and produce new contributions to knowledge. In terms of my PhD this involves devising methods that can be applied to develop an understanding of something that would not usually be associated with art practice.

It would be remiss of me not to mention that my PhD supervisory team is comprised of Dr Simon J. Harris and Dr Dean Kelland, both of whom are well placed to advise on the residency having made huge contributions to Ikon’s Art in Prisons programme.

Your work is particularly interesting as your research considers the effects of your chosen medium (light) on prisoners’ health. The residency is also underpinned by creative evaluation, facilitated by Ikon’s Public Health Research Officer, considering the effects of art practice on prisoners’ health and wellbeing…

I am really excited about the work here because I genuinely think there could be beneficial outputs in both respects – the Public Health focus is so important and not purely for a prison population. The data being collected in terms of health and wellbeing could apply to anyone. The workshops entail an informal art programme with a degree of freedom to explore, but apart from that it’s a lot to do with being a space to talk and engage with other people. It is a safe space and for some the only time they will be off the wing all week.

The group I am working with are just as enthusiastic about my work as their own and there are some really valuable conversations taking place. I discuss my ideas with them and appreciate their input. All work is reviewed with the group, they really need to be part of the process of making because it reflects their experience and not specifically mine. If I want to pop out for some sunshine, I am free to do so, but their time is limited and formalised. The impact on staff is also a concern. I have repeatedly read a Guardian article published in 2002 regarding the lack of natural light in prisons causing harm to prisoners and prison staff. I remember sitting in the studio in April, so it was still cold and not very bright. The studio is basically a concrete block with no windows with a couple of fluorescent lights. I’m not going to lie, for someone who draws their inspiration from sunlight, I was pretty miserable for a brief moment, sitting there alone. But it was when I realised I needed to go and look for the daylight that the research began to flow.